Part I: Composition in Music Therapy

Introduction

If you are working actively in music therapy sessions, spontaneously creating music with your clients, then you are likely already composing. You're using elements of your musical craft to create themes, harmonic progressions, or musical forms that support clients and move them toward greater well-being. Clinical composition is one aspect of "clinical musicianship", a term defined by Nordoff and Robbins in the following way:

“...the dedicated, utterly contemporary confluence of the art of musicing and the craft of musicing in the service of therapy.”

Simply put, in composing music for therapy, we focus our musical creativity on the therapeutic needs of our clients while remaining sensitive to what in music will engage them.

There are various ways in which we can compose for therapy. All are valid ways of working:

Composition "in-the-moment": Spontaneous musical improvisation (in session) in which you create a musical vehicle, in a fully-realized form, which captures the needs/actions/feelings of your client.

Compositions developed from previously improvised Ideas: Particular motifs emerging in sessions, such as a melody, a certain style, or an engaging rhythm, can be notated afterwards and developed more fully outside of sessions.

Composing completely "on your own": Writing music entirely outside of a session, with your client’s process, character, clinical needs and preferences in mind. Composition naturally involves improvising or creating ideas vocally or instrumentally; recording and/or notating it; and then developing the idea over time, outside of sessions.

My focus in this course (as well as in Course II) will be on the third approach—the value of introducing goal-directed compositions to clients and the process of composing instrumental pieces "on your own."

Music therapists traditionally use familiar, pre-composed songs and activities in sessions. Similarly, clinical compositions that we craft ourselves can become a dependable facet of the therapy process, providing consistency and satisfaction for the client from week to week.

When we offer pre-composed music containing specific opportunities for playing or singing, we are entering into what Kenneth Bruscia calls a “Re-Creative” aspect of music making (Bruscia, 2014). Inviting a client to participate in instrumental music possessing special parts for various levels of participation can provide positive challenges and a sense of accomplishment if done with sensitivity to the relationship and clinical process. Some clients may be unable to enter into musical activity on their own, and a facilitated piece can help guide them. Importantly, the use of specially composed and facilitated instrumental pieces can serve as an important step in leading those individuals towards a greater ability to express and improvise through music.

Throughout this course I wish to emphasize the following principles and core values of clinical composition as I see them:

Specially crafted compositions can enhance opportunities for musical involvement, expression and interaction.

The use of Clinical Composition can facilitate growth in specific and sometimes unexpected goal areas.

Equal consideration of both the musical and clinical makeup of compositions is vital in order to bring clients a satisfying, motivating and clinically effective experience.

Awareness of and attention to all facets of music by the music therapist can lead to a parallel process of creative engagement for you and your client. What this can bring is truly the unique offering of music therapy.

Vignette

The following example illustrates one way in which a pre-composed instrumental piece was integrated into music therapy sessions. I worked with an adolescent boy whose family encouraged him to begin therapy because of his deep interest in music. Intelligent and highly verbal, he was born with cerebral palsy, and his physical challenges led him to be especially self-conscious and withdrawn during this time in his life.

I anticipated that therapy goals would eventually include: 1) developing relationship and confidence through musical play, as well as 2) increasing the ability to express his feelings musically and/or verbally. As sessions went on, however, he seemed guarded and expressed very little personally, verbally or musically. He usually entered the room with headphones on, listening to music in order to, as stated by him, "shut everyone out.” Around this time, I composed an instrumental piece, “Lydian Dream” with parts for triangle, metallophone, and reed horn. The music requires simple responses but offers enrichment through a variety of timbres and the particular tonality.

“There is a gentle flowing momentum in the triple meter, the accentuation of the bass motif and the colorful harmonic progression. All combine to carry the player’s participation. Every such piece offers the participant a journey through a musical landscape. The serenity of the Lydian mode creates the mood and climate of this journey. The fact that a client becomes closely involved in making music with the therapist involves him or her ever more deeply in realizing the musical experience.”

When I introduced "Lydian Dream" in session, the client was open to participating and seemed to feel an immediate affinity for the musical-emotional atmosphere of the piece. He concentrated and played the instrumental parts with care. After a period of silence, and a visible change of mood, he opened up verbally about his difficulties. In this instance, the composition offered a musical experience which seemed to touch on feelings he tried to avoid but needed to express. Creating or offering such music is just one of the ways in which composition can enrich the therapy process for our clients.

Historical Context and Clinical Rationale for Integrating Composition in Music Therapy

As a young musician and psychology major exploring the field of music therapy, I was fortunate to come upon the work of Paul Nordoff and Clive Robbins. Their creative, improvisational approach to individual music therapy beginning in 1959 had a significant influence on my career and life. So too, their compositions created for the special classroom setting in which they first worked together were inspiring and unlike anything I expected to hear. (See Part IV Resources for texts on the Nordoff-Robbins music therapy approach).

Creative depth and attention to musical detail are evident throughout their recorded clinical work, books and compositions for therapy. As I wrote in “The Primacy of Music and Musical Resources in Nordoff-Robbins Music Therapy,”

“Nordoff and Robbins composed songs and instrumental pieces prior to sessions that, in their quality, clarity and beauty, serve as models of musical form fashioned with developmental challenges embedded within.”

This music originated from the synergy of Nordoff’s sophisticated musical palette, Robbins’ intuition and wealth of experience in special education, and the particular needs of each child. (Please note: While most of their writing refers to “children” or “students”, the ideas are applicable to all age groups.)

Musical forms—whether improvised or fully pre-composed—encouraged emotional engagement and positive focus as, through them, the team facilitated a process of creative work in a musical community. The practice of offering musical pieces with special instrumental parts enabled Nordoff & Robbins’ students to become music makers. They learned to handle instruments, developed the ability to play with expressive flexibility, shared musical activity, and through this gained new developmental skills.

In Defining Music Therapy: 3rd Edition, (2014) Bruscia describes some of the demands involved in re-creating music in general.

“Singing or playing pre-composed music involves the body and the senses in the same ways as improvising. The main difference is in the degree of physical structures and demands required to play or sing an existing composition. In improvisation, there is no musical model; the improviser literally makes up the music moment-to-moment and therefore is able to adapt the music somewhat according to his own physical capabilities. In contrast, when re-creating a piece of music, the singer or instrumentalist has a model; they are expected to fit within the physical structures and meet the physical demands built into the composition by the composer. They have to produce the correct notes in the correct rhythm and tempo and in the designated timbre and dynamics.

This requires the person re-creating music to use and control his body to create sounds in the way specified and in the amount of time allotted by the composer. Vocal and instrumental performers cannot adapt the composition to fit their physical capabilities; they have to develop their capabilities to meet the physical demands of the composition.”

Bruscia goes on to describe the implications for integrating compositions in music therapy sessions.

“Given all that is involved, singing and playing pre-composed music can be used therapeutically to establish, maintain, and improve the ability to use and control different parts of the body, to develop and integrate sensorimotor skills, to structure or modify behavior, to promote temporally ordered or time-appropriate behavior, to build self-discipline, and to teach working toward a goal with perseverance and self-confidence. ”

In clinical composition, parts can be written that enable experiences of success and also of challenge. It is important to note that, in a music therapy context, the work of mastering a piece of music is viewed as a gradual musical/therapeutic process. Clients will require time to grasp, internalize and participate fully. Attention must be paid to how the client is relating to the overall experience and, as in all our work, it is crucial to remain sensitive to the balance of creative and interpersonal process.

Musical Content and Its Impact on Therapy

In 1971 Nordoff & Robbins wrote Music Therapy in Special Education, currently in its second edition published by Barcelona Publishers, who has kindly granted permission to share content from several sources. Throughout the book the authors remind us of the very heart of music, the art in the practice of music therapy. The book is filled with practical musical wisdom, including chapters on singing, instrumental activities, and musical plays. Whatever your client population or music therapy approach, there are likely ideas in their books that can enrich your practice.

Consider the context of their work: a very early period in our field, a time of exploration into what music therapy could be, and the presence of proscribed views of music for children.

“Music is a language, and for children it can be a stimulating language, a consoling language. It can encourage, hearten, delight, and speak to the inmost part of the child. Music can ask stimulating questions and give satisfying answers. It can activate and then support the activity it has evoked. The right music, perceptively used, can lift the (handicapped) child out of the confines of his pathology and place him on a plane of experience and response where he is considerably free of intellectual and emotional dysfunction.”

The team boldly advocated for providing the same musical richness in therapy with children that any of us would desire in the various musical contexts of our lives. One aspect which they emphasized is the use of harmony.

“The harmony in many children’s songs consists of two chords-the tonic and dominant-and possibly a third—the subdominant. The harmonic element of music directly affects our emotions; when it is consistently this restricted the children receive limited musical-emotional experience. This is especially true if the chords are played only in the closed root position. More open voicings will add tonal breadth and fullness. These same harmonies can become more dynamic and varied in emotional effect when inverted. They then provide harmonic support-yet keep a melody moving by withholding the sense of stable balance the root position triad carries, until this is right for the melody.

Songs with limited harmonization can be given increased vitality and emotional richness by the addition of secondary seventh chords, those on the 1st, 2nd, 3rd, 4th, 6th and 7th scale tones. These may be used in both root position and inversion.”

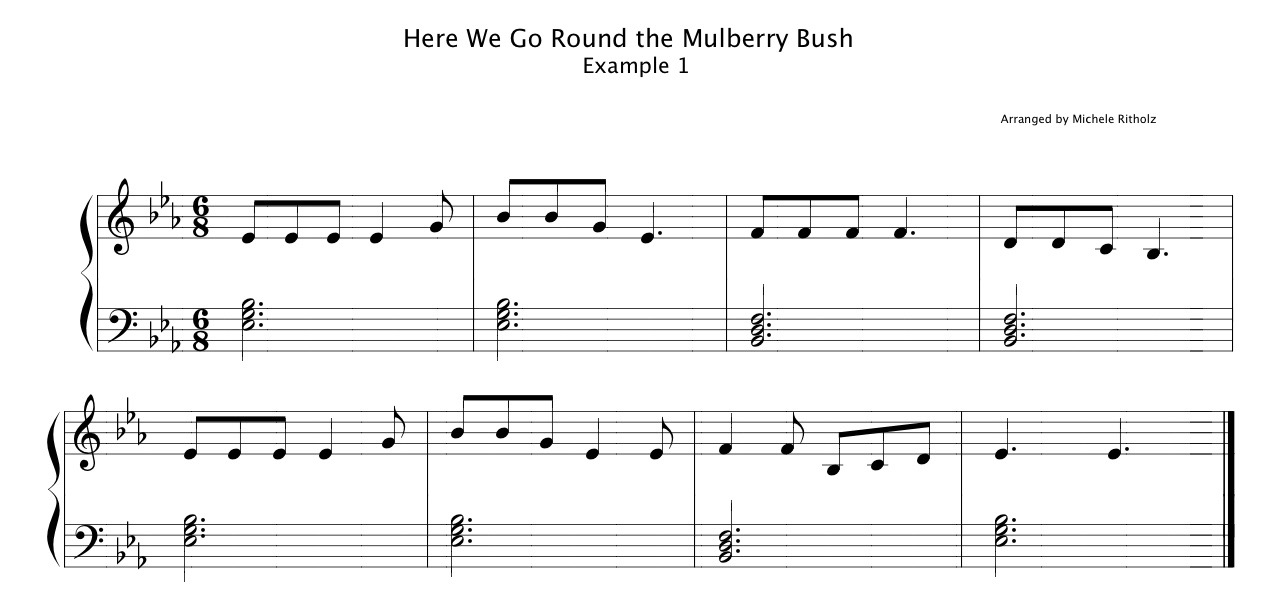

In Music Therapy in Special Education, the traditional “Here We Go 'Round the Mulberry Bush” is used as an example of a popular children's song, in a major diatonic tonality, that is often played with 2 primary chords, I and V in root position, as in the following:

Now listen and play Example 2 offered by Nordoff & Robbins (p.31) which provides a different musical experience with added tones and inversions. If you are playing on a guitar, work to use the same harmonies and inversions as the piano score. (Please note that the roman numerals in mm.1 and 7 for the II7 chords omit the inversions, but please play as written.)

Nordoff and Robbins continued to write about the impact of harmony as well as melody in their later book, Creative Music Therapy: A Guide to Fostering Clinical Musicianship (Second Edition, 2007, Barcelona Publishers).

“Harmony does more than harmonize. How it harmonizes is more to the point. The balance between tension and resolution in a song’s harmonies determines the quality of its movement in time, how smoothly, gracefully, excitingly, joyfully, or thoughtfully it flows, and how clearly and cogently its content is enhanced. The character of its sonority will affect how satisfyingly it fills the feeling space of the moment.

Harmony animates the melody and the melody invites the singer: if the harmonies have movement written into them, they keep the melody moving and directly draw the singer into song. Tension is created by the so-called dissonant harmonies: the seventh chords, superimpositions, and suspensions; there can be soft dissonances and forceful dissonances, lesser or greater tension, different qualities influencing how a melody is supported and propelled in time. Resolution comes from the consonant chords: the holding stability of the root position triad, or the subtler pausing or transitioning effect of an inversion. ”

“A well-structured dynamic harmony intimately suited to a song’s melody and expressive content can make all the difference in how livingly a song is experienced and sung. Other factors such as the voicing and density of chords, the rate at which the harmonies change, will all affect the singability and impact of a song.”

Here is one more example of the traditional song you played earlier. It contains more quickly changing and sometimes unpredictable harmonies, as well as more dissonance. Play, and consider the various experiences these variations create in you.

Arranged by Michele Ritholz

We have just touched upon some of the basic components of music, involving tonality (Eb Major), chords (content, position, spacing of tones), and chord progressions. Our choices as music therapists are broad. With awareness, we can work to bring creative contrasts to our compositions and improvisations. Expressive elements such as rhythm, tempo and timbre are just some of the additional ways we can convey musical meaning and motivate engagement in therapy. While it is not possible to touch in depth on every element of music in this course, it’s valuable to visualize the musical palette available to us. In this way we can stay conscious of our many options as composers (and improvisers) and avoid limiting the music for our clients.

Musical Palette:

Basic Musical Components

Tones, Intervals, Melody

Scales, Modes, Idioms

Chords—their content, and the position and spacing of tones

Chord progressions

Phrase structure & Musical Form

Expressive Variations

Tempo & Dynamics

Touch/Articulation

Register

Timbre

Rhythm & Meter

Texture

Character or Mood

Let's focus for a moment on the expressive variations of Rhythm and Tempo that we can consider in writing a composition. What kinds of musical experience would be constructive for a particular person with whom you are working? Consider how you might compose in order to encourage greater attention and interaction.

Will the client or group benefit by learning to organize themselves through a musical piece that highlights the basic beat or pulse?

Is there an individual who would be intrigued by imitating a rhythmic idea in response to one played by the therapist?

Contrasts of slow and fast tempos might be captivating.

To enhance the experience, perhaps the distinct timbres of drum and cymbal would be engaging.

Playing along with the natural rhythms of sung lyrics (melodic rhythm) might bring clarity to the experience, and encourage confidence.

We can base a composition, in any scale, mode or idiom, on those expressive frames. As Nordoff & Robbins write, in Creative Music Therapy,

“In using songs for this purpose be attentive to the expressive components that vivify their melodies: dynamics, crescendo, diminuendo, ritardando, rubato, the fermata. Exaggerate the components to increase attentiveness or to heighten pleasure in coactivity; “underplay” them when structural stability is necessary to help a child grasp their rhythms.”

As we begin to create a composition, we assess a client’s present level of functioning and consider the next steps in his development, determining what musical elements would help achieve these.

“It is uniquely important when engaging a child’s inborn musicality to respond to his musical enthusiasms, gratify his eagerness for musical pleasures, and lead him into the adventures of gaining musical achievements. For example, with a child who tends spontaneously to beat the rhythms of melodies, select songs for his beating which differ in time signature, rhythmic structure, tempo, mood, and key. A child so inherently disposed to melodic experience can find a deeply personal fulfillment in his capabilities being activated, developed, and made communicative.”

We’ll focus on additional musical elements through the study of several compositions in “Musical Examples and Analyses” Section II.

Using Compositions in Music Therapy Sessions

In the introductory section of Themes for Therapy: New Songs and Instrumental Pieces, editors Michele Ritholz and Clive Robbins describe the practice of composing, and the impact of this music on clients:

“Composing or improvising songs and instrumental pieces for children is an inevitable part of the practice of creative music therapy. The themes offered…are a natural outcome of meeting clients, their needs, and their abilities, in and through music. The pieces originated in therapists’ responses to individuals or groups and are therefore truly client-inspired. All were created at various stages of therapy to reach out, express relationships, and at times celebrate achievements. Much of the music also facilitated the growth of group cohesion, so creating a healthy working environment in which each client’s activities and discoveries became shared and enhanced. To the extent that an individual or group identified positively with a particular song or instrumental activity we saw that these pieces had the potential to play unique roles in courses of therapy, and so in the development of clients’ lives generally.”

Additionally, experience has shown that while we may compose a piece for a specific person, it may be very effective with a different individual.

“Not every song used in individual music therapy has to be created specifically for the child in question to be effective. The creative adaptation of an existing song or melodic idea — triggered by a therapist’s insight into a child’s needs at a moment in therapy — may well provide a needed entrance into a new experience. Also, a musical idea or song originally improvised to structure a certain mode of rhythmic work, or to create a mood, or as a welcome with one child — or possibly even a group — may be used or adapted, as appropriate, with another individual, whether or not for a similar purpose, into enjoying participation.”

Vignette

The use of instrumental compositions enhanced the music therapy group process with 3 lively children ages 5-7. Two of the boys were diagnosed with PDD (pervasive developmental disorder) and the third boy coped with a rare condition which led to malformations of his skull, impaired vision and and decreased hearing. Despite individual challenges, each child showed particular strengths, and a special joy in participating in music. Our therapy team's humanistic, client-centered and flexible approach created an environment in which each child could thrive and build relationships with us and one other.

Early on, the children related more fully with their therapists than with their peers, became easily overexcited, and had difficulty with attention. Therapy goals were defined yet evolved as each child--at their own pace--became involved in musical experiences involving pre-composed and improvised songs and instrumental activities.

The following therapy goals became the emphasis of group activities:

1. To develop greater awareness of and empathy for peers

2. To strengthen social skills, by waiting a turn, listening to others, sharing instruments, playing together

3. To increase and use expressive language, in improvised and pre-composed songs, and in transitions between activities

4. To play with flexibility and control, i.e. in a range of tempi and dynamics

5. To experience joy and success in shared musical activity

Introducing and working on a song such as "Beat! Beat! Beat the Drum!" (Ritholz, Themes for Therapy, pp.74-75) served as a vehicle for increasing their focus, physical control, dynamic expression, and positive cooperation. Through its upbeat mood, contrasting B section, clear phrasing with easily perceived places for participation, and use of inversion, dissonance and harmonic surprise, the song motivated and challenged the group. Compositions such as this were worked on over time, and the group happily anticipated playing and achieving their parts each week.

Importantly, when the children made suggestions verbally, or played variations musically, these could be taken up in repetitions of the song. The atmosphere was energetic, cooperative and joyful much of the time.

The Interplay of Composition and Improvisation

Music therapists Alan Turry and David Marcus describe the advantages of including compositions in group music therapy in the chapter “Using the Nordoff-Robbins Approach to Music Therapy with Adults Diagnosed with Autism” in Action Therapy with Families and Groups: Using Creative Arts Improvisation in Clinical Practice, (Weiner & Oxford (Eds.) (2003). They use the term “realization” to describe the process of recreating a specially composed piece of music that has particular parts for players.

“We call the action method that uses pre-composed pieces in the process of group music therapy realization. In actualizing the potential of working in a musical environment, the action method of realization offers the following particular benefits:

Stimulation: The most obvious aspect of the realization environment that makes it a unique source of stimulation is that is an aural/tonal environment. Hearing can be every bit as important as sight in functioning in this environment, and often the former supersedes the latter. In fact, many of the cues for musical participation can have a threefold nature: They can be aural, visual, and verbal. This overabundance of directive stimulation can have several beneficial effects. The intensity of such stimulation can motivate clients to be more active. It can help in diverting the attention from internal preoccupation and self-stimulation and focusing it on outside stimuli. It also can help sustain and increase the intensity and duration of concentration. Finally, the clarity of such stimulation can be reassuring to the client, leading to greater confidence and higher levels of activity

Socialization: Realization necessitates a basic social awareness of other members of the music therapy group. The initial awareness of the leader (or therapist) as the person who facilitates by giving musical directions expands to include the therapist at the piano and the other group members. Awareness of others may reach the point at which it is independent of the leaders’ activities and persists in the absence of music. Clients become aware of each other as people and peers as well as fellow musicians.

Community: A sense of belonging, of camaraderie and cohesion, develops with the memory of the successful completion of the pieces and the anticipation of new experiences. The aspects of participation that are common to all help to form a bond: the risk of facing the challenge of attempting things that are untried, the willingness to work to overcome individual difficulties for the sake of the group, the willingness to persevere in one’s efforts in order to experience a sense of musical completion, and the ability to tolerate and appreciate differences in levels of participation.”

Experiences with specially designed pieces can enable greater participation in improvised musical experiences. Marcus and Turry write:

“Realization emphasizes the awareness, perceptions, and behaviors that enable the clients to make pre-composed musical statements at prescribed times. Improvisation uses the prerequisites for realization and further expands awareness and perception to enable the clients to make spontaneous, self-expressive yet relevant musical statements when they themselves feel them to be appropriate. Full participation in realization is a developmental step in the process that leads to full participation in improvisation.”

The authors’ experience with a group of adults with varying levels of ability leads to the following observations:

“Realization brings assurance and reassurance. As clients gradually become acquainted with and master their parts, their sense of assurance grows. As the various parts are woven together, they become aware of the interrelation of the parts and the resultant whole, and their assurance grows still further. As they change parts and recreate the piece several times, they are reassured with each realization of their own abilities as individuals and as a group.”

Turry and Marcus note that clients may naturally lose interest in such music over time, at which point improvisation may be clinically warranted.

“Although realization may become stale, it usually has a favorable effect on the music that is subsequently improvised. The experience of realizing carefully crafted melodies and consistent rhythms leads to coherence in the freely created music that is immediately noticeable.”

Concluding Instructor Remarks:

Whatever the musical medium we offer in sessions, we need to do so flexibly in order to invite participation, support client initiatives and make musical changes as needed. This is especially important to remember when bringing in pre-composed music. Music therapy students and therapists often speak of “getting stuck” in written music, as if its mere presence creates a block against spontaneity. This may stem from the way we have previously learned music, or the ways in which we experience the pre-determined structure of musical form, with its particular beginning, middle and end. This mindset can cut us off from the possibility of creating something new in the moment, the opportunity to form new music that flows from the original composition and the client’s responses to it.

COMPLETE PART I ASSIGNMENT ON YOUR SAVED GOOGLE DOC BEFORE PROCEEDING TO PART II